Origami: continued overleaf

When I tell people I've been doing origami, they love to say 'Mindfulness!' And I think, well, you're wallpapering over a cultural form with hundreds of years of history, which is a visual art, an object of wide-ranging mathematical study and a branch of engineering that'll help get us into space. The art side is what interests me most of all. That's split into representational origami (animals, vehicles, sea life, dinosaurs ...), abstract decorative origami, crafty practical objects like boxes and vases, modular and macro-modular origami based on polyhedrons, and corrugations and tessellations. I'll get to all of those.

Beth Johnson, Ewe

I like it in the way I like playing through and uncovering piano music. Origami (specifically: folding paper according to designs made or discovered by other folders) sits pleasantly between actually creating something (way too difficult) and passively consuming media. You can design things yourself, or you can make them, or you can look at and appreciate what other people have made. I equally enjoy looking at diagrams and picturing the folding of designs I'll never make time for - a bit like browsing shops full of books I’ll never read, which is also a very informative and enjoyable way of spending an afternoon.

A vase by Robert Lang

The Spread

Origami isn't that old. People have been folding paper for as long as there's been paper, yes, but paper itself hasn't been around that long: about one millennium, as we know it. And while it has, it's rarely been something so disposable as to use to make art objects that are are meant to fall apart..

The word is Japanese - it means paper folding - but it's wasn't practised uniquely or originally in Japan. I think the first book on paper folding was published there, which is why the name caught on, but when origami, crane-like, took flight in the 1970s, it was an infrastructure formed between the US, Latin America, Spain and the UK, as well as Japan, which enabled its rapid technological progress. In the past 20 years, both computer-aided design and online information sharing gave origami the mega boost that got the first auto-folding solar sails into orbit.

More by Beth Johnson

Mathmo-origamist Robert Lang is a big exponent for the role origami plays in furthering the human species. Origami now has delegates among the engineers hoping to replicate nature's feats of folding (insect wings and DNA) in the same way AI scientists are trying to engineer new life. That's very impressive, but I'm a little suspicious when STEM is phoned in to justify people getting really into things which seem mostly to do with aesthetics. For most folders, most of the time, it's the aesthetics of origami that hooks them: its fragile beauty, its cross-cultural meaning, its power to represent nature and the pleasant philosophical questions about beauty, design and creativity that it smears around your mind during and after a quite 40 minutes.

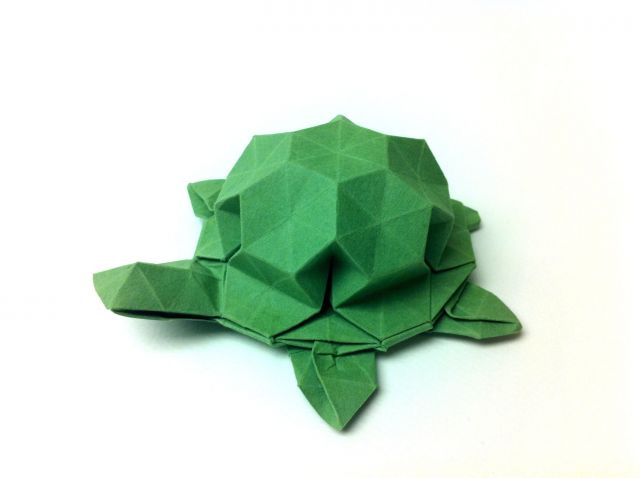

Representational Origami

There's some origami I have always been averse to, particularly Father Christmases, violin players and anything made to contain beads. (Maybe I'll think differently in future, but fortunately, nobody asks you to choose.) Animals are great though. It's awesome to look at a paper model which implausibly captures the creature it represents. Then, when you know some of the classics, it's fascinating to compare impressions, simple or complex, abstract or lifelike, which each designer has imagined. Among my favourites are Hideo Komatsu, Joao Churrao and Rui Roda. Being such a late-blossoming art form, origami skipped the Modernisms of the early 20th century; because of this, there’s little baggage that comes with representation or abstraction — all of origami’s strands develop together.

Fish Guy, by Joao Charrua

Within animal design, there are practices dedicated to mammals, fish and insects, as well as spiny dinosaurs, creatures with no spines at all, and the full catalogue of fantastic beasts, with books dedicated to every variation of dragon, wyvern and wyrm.

Then there's plant life, studies of masks, busts, robots and skeletons, and a load of mechanical things besides.

Satoshi Kamiya’s Divine Boar

I especially enjoy representational origami that draws on techniques from corrugation, tessellation and spirals. I recommend a Google-dive into the work of Beth Johnson, Tomoko Fuse, Hideo Komatsu and Toshikazu Kawazaki.

Tessellations

This is the branch of origami design exploring infinitely repeatable patterns that can be folded out of one sheet of paper. Both tesselations and corrugations comprise of repeatable blocks, but in general tessellations can be made to lie flat, whereas corrugations play on their 3D-ness and interaction with light. There are also fractal tessellations, such as Shuzo Fujimoto's Hydrangea, which can be repeated to become infinitely small or large. What links them all is that they're fascinating and beautiful, and when you start folding them it's easy to feel like this whole business of living our lives side to side and up or down isn’t exactly the full story.

Brother tessellation, found by Ilan Garibi

Tessellation folders like Ilan Garibi and Eric Gjerde talk about how they discover, rather than design, tessellations: the design is and always has been there (or it has been, at least, from the paper's perspective.) It's probably the fastest-growing and most recently developed strand of origami, with only a handful of books published. Garibi's upcoming Tessellations 2 is subtitled 'Origami Tessellations for Everyone', which is characteristic of the tessellation evangelism contemporary origami is bearing witness to. I don't think tessellations are for everyone, but for 'anyone'? Maybe.

Relatedly, there's the field of making curved folds in paper, stemming from the work of Dave Huffman (pictured) and recently popularised in Jan Mituni's Curved-Folding Origami Design. These techniques have been adapted into spectacular single-sheet tessellations by artists like Ekaterina Lukasheva, who is dually remarkable as a master of the modular Kusudama.

A curve-folded tessellation by Ekaterina Lukasheva

Modular Origami

This is the stuff you see strung between the escalators in John Lewis at Christmas, naively beautiful and reflecting shop lights at delicately varied heights, and inspiring terror at the vast emptiness beneath.

Malachite variations, by Ekaterina Lukasheva

It involves cutting up squares of paper into slightly smaller squares, and folding usually 30 units, which you then reconstruct in some variation on a Platonic solid, (or a combination of them.)

David Mitchell is responsible for superb, endlessly varied designs with names like Electra — which speaks straight to the heart of the 1970s boom— Sappho and Thingumy. Tomoko Fuse's Unit Origami has, since the 1990s, been the book that gets in the crowds. It's really the only origami you can do while paying attention to something else: English language TV, a concert broadcast, a radio play. But putting together the pieces can be maddening and it's easy to loose track of time while you hold together an increasingly unstable, quivering dome of paper. When they're finished though? All the mess and tension dissipates. It’s a secret memory between you and the paper ball.

Shells by Tomoko Fuse