Monday 1 April

I read through Korngold’s Op 3 Fairytales, after hearing them on Radio 3 on Sunday night. I noted when listening how they blend folk melody with additive harmonies and Korngold’s dense, characterful piano textures. To play, I found them overlong and overcomplicated. But he composed these pieces when he was 12, so I’ll allow it.

While playing them, on the work piano in the morning, I was listening to E Nesbit’s Five Children and It as an audiobook, hearing how the five children wished to look as ‘beautiful as the day’ but discover (like the Invisible Man) that seeming either very beautiful or not seeming at all doesn’t give you a free pass through life. Nesbit’s nib is always sharp but her intended audience is children, though she criticises adults often, and particularly how they lie to children; they tell children only moth larvae eat clothes, but when children aren't around, they will talk to other grownups as if the moths themselves do the eating. I wondered what is more juvenile: writing by children or writing for children? Music by children or for children? For one art form it seems like a fundamental aesthetic distinction, and for the other it seems irrelevant.

Later, a 1983 radio documentary ("The Golden Age has Passed" - a radio documentary on Bax by Michael Oliver (youtube.com)) put me onto playing Arnold Bax’s music. Bax picked up the topics of fairytales in a Pre-Raphaelite way, for how they feel and what they recall, rather than what meaning they infer. I played through the Russian diptych: a nocturne evoking a May night in Ukraine and a Gopak. Like the Korngold, these too were long and complicated and Bax didn’t have the excuse of juvenility. His problem and his confoundment (which was also that of Ireland, Bridge and company) was Debussy - who managed everything Bax and friends wanted too with ease and simplicity, usually in under 4 minutes.

On Monday night I played through a selection of Scarlatti sonatas, experimenting with swapping staccato and legato between hands, and choosing one beat per bar for halving the tempo. This all went well and I decided I’d look at these sonatas again tomorrow. (I wouldn’t.)

I wondered whether recent practice of ‘never articulating the same way twice’ and ‘not looking at my hands’, which had made Baroque music constantly interesting, would also endear me to practising later music, like Balakirev’s The Lark. When I tried it, the middle Arabesque section came more easily than ever. It was relaxed and accurate; I could listen to the melody without my eyes and nose darting in different directions. It is in B-flat minor, which I’ve come to think of as ‘too serious a key for the likes of me’. But it is mystical and seems very Russian.

Tuesday 2 April

I started with Bach’s B-flat minor P&F from the second book of the well-tempered clavier. I opted for book 2, being already familiar with (and not much endeared to) the B-flat minor from book 1. I was not endeared to the book 2 either. It’s a lengthy sinfonia and fugue of the kind that pad out Bach’s cantatas.

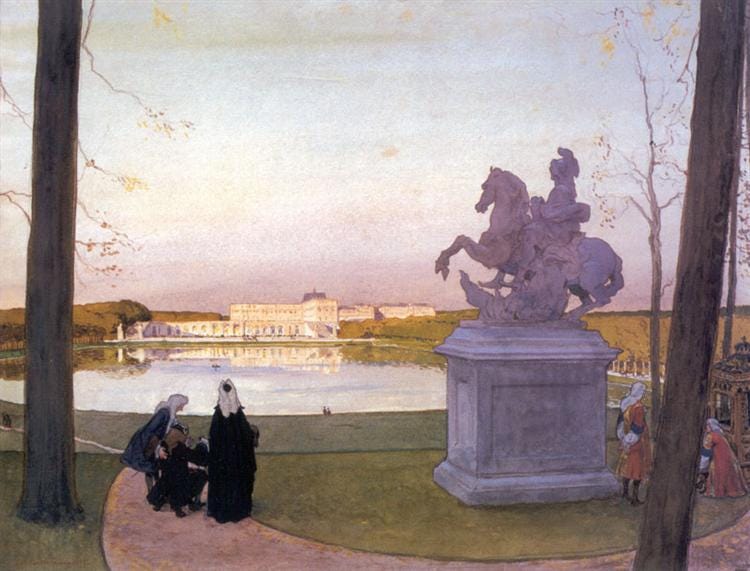

After, I played two Balakirev waltzes and particularly liked No 3, a ‘Valse impromptu’ in D major. It’s impromptu aspect is its flimsiness. At each intake of breath, one fears it might never exhale again, like one of Liszt’s valses oubliees or Saint-Saens' ‘Valse nonchalante’. It is music that lives in the impossible Paris-St Petersburg of Alexandre Benois' Versailles paintingsA.

Wednesday 3rd April

I hadn’t settled on whether or not to go into the office as I was a little indisposed, but every time I have a cold and have to make this call, I worry that I might, after being off sick once, spend every day after trying to work out whether or not I need a sick day. It is simpler to push through and probably not any more difficult, if you’re going to feel indisposed anyway.

I listened to Muriel Spark’s Loitering with Intent on my way in and kept listening to it when I practised (in the course of the day, it would turn out to be a rare 5-star read). And I started with Chopin’s Op 6 Mazurkas. This is his first set and, like the first book of Mendelssohn’s Songs without words, is one of the best. Chopin’s Mazurkas became more artful in the years that followed, but their personality was there from the start, like he was trying to build a colour palate and just picked all the right colours on his first try. I compared them with Mazurkas by the Scharwenka brothers, Philipp and Franz Xaver, which were composed in the second half of the 1800s. I like them plenty, but they’re formal compared to Chopin’s; really square, as dance music maybe should be. Op 6 seems to have been composed en plein air.

I followed this with practice of the Gigue from Bach’s E major English Suite, and then a play through (starting with the back page first) of the finale from the Italian Concerto. The piece promises good fun without asking any questions of it, but it remains perplexing to me. It is composed like a transcription of a Baroque concerto for orchestra, but that concerto which inspired it doesn’t exist.

On a piano the piece is removed once more from its source material, almost like Rhianna transcribed for solo flute. When I hear this played, it’s as if I’m not hearing the music itself but trying to imagine what it’s based on. Inclusion in an anthology of graded pieces can also have this effect. There’s something about ABRSM editing that cuts music out of the world. GCSE exam boards do a similar job with their poetry anthologies, which present Elizabeth Barret Browning on paper that seems meant for sticking up next to a swimming pool. I have no issue with musical works whose ideal performance can only be imagined. Maybe this is this one of them, or maybe I just need to listen to the right harpsichordist.

Wednesday night I played the G major fugue from ‘book one’. It was one of a small number I had saved on my MP3 player back when there were MP3 players. Then I found it brilliant, but practising it makes it less and less so. Ideally I’ll learn to play it competently, then forget about it for several years, then come back to it and play with brilliance.

Afterwards, I dipped into the book of miscellaneous Schubert I got before Easter in the Oxford Oxfam. It includes the E major adagio which has (what is rare for Schubert) exactly the right amount of awkward events and is otherwise like a beautiful movement from a Mozart concerto - maybe it is the adagio of a piano concerto Schubert never wrote. I also played the supposed finale of the unfinished E major sonata until it nauseated me. It is not a great piece, or even a suggestion of one.

Thursday 4 April

I listened to Oblomov on my way in, Ivan Goncharov’s 1859’s precursor to My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and then started practice with the E-flat minor sonata by George Pinto, who I don’t imagine spent much time in bed. Pinto was an English composer who died aged 21, in 1806. By then he was already a prodigious performer and had composed a handful of piano sonatas as good as John Field’s. I think of him as a musical Keats, though even Keats made it to 25.

I made a note to read Hyperion then returned to playing Bach’s G major fugue. I didn’t know the passages I’d practiced the night before any better, so took a different approach: hands separate, while trying not to make assumptions about what the notes were or could be, especially if they were ones I didn’t intend to play.

In the evening I played Bach’s C# major fugue from book 1 in a new favourite edition available on IMSLP. It’s by Orlando Morgan and has the best of 1920s editing practice (suggested fingerings and enharmonic transposition) and little of the worst (alternative readings, phrase markings and inserted lines of music). It must be annoying for the people in my sonic environs that I’m into Bach. I sympathise, as someone who complains when people play Bach as if no other music exists. The trouble is that when you do play Bach, it really fills a lot of space, and it can be hard to remember that other music does exist (and if it does, then why?)

Afterwards, I played Liszt’s ‘Deux mélodies Russes’. Both are arabesques and neither are as good as Balakirev’s The Lark. The second, ‘Chanson bohémienne’, has a Carnival-of-Venice charm without the difficulty of Liszt’s opera transcriptions. I don’t know whether it is a lovely concert piece or a bit boring. I assume the former, since it is one of the three Liszt pieces teacher Raymond Fischer recommended learning and the other two were very worthwhile. Raymond sadly died in February this year, at 95 (Concert pianist and renowned teacher who was devoted to a musical life (smh.com.au)). Playing Liszt after Bach is a pleasure. Liszt lets you make music so freely it feels like cheating.

Friday 5 April

I downloaded a PDF of Japanese Sonatines from the twentieth century to play at lunchtime (https://www.pianophilia.com/phpBB3/download/file.php?id=31863). The Sonatine has potential to communicate the musical styles of the twentieth century with directness. Composers have access to the full expressive toolbox, and a few limitations to focus their efforts. Sonatines can be abstract or descriptive. They must be simplistic but they can be fiddly, responsible for teaching something to a student without frightening them away. They are never too long. Effects must be achieved with “the notes themselves”, the basic techniques of melody, harmony and counterpoint, and can not rely on a composer’s hope that they’ll be played with brilliance or sonority.

But what happens most often is that a sonatine’s expressive edge is sanded off somewhere in the production line. They converge, aesthetically, at “Prokofiev in Miitopia”. Looking at the scores of the Japanese Sonatines, I suspected these were situated in that unfortunate spot, and playing them confirmed it. Still,I’d like to hear other music by Toroque Takagui and Tomojiro Ikenouchi.

In parallel with my investigation of B-flat minor, I’ve been wondering whether Sergei Lyapunov (1859-1924) wrote good piano music. He was the son of astronomer Mikail Lyapunov and brother of mechanician Aleksandr Lyapunov. I’m not sure how you qualified being an astronomer or mechanician in the 1800s, since no one was obligated to show what they could do with their astronomical or mechanical theories then. Composers at least had to prove themselves, to write some music and for it to sound good.

Lyapunov is best known for his Op 11 Etudes of Transcendental Execution and his music is characteristically difficult. I played his Op 41 Suite de Noel and Op 65 Sonatine, which are among his easier pieces, but with the virtuosity shaved off not much is left. To check I wasn’t asking too much of any piece of piano music, I recalled Scriabin’s B-flat major prelude from Op 11 (Scriabin 24 Preludes Op.11 - No.21 in B flat major (youtube.com)) which can calls forth a rich expressive world and invites almost any player to do so. I will try Lyapunov again but I fear he hoped too much that performances of his music would be sonorous or brilliant.

I wanted to share a diary of one week of playing the piano. My playing isn’t always so various. Sometimes I practice the same thing every day and make it better. Sometimes I practice the same thing each day and make it worse. Most often, I play like I’m watching TV, or browsing a bookshop, or exploring an abandoned mansion in a temperate forest. I wanted to record for myself as much as for any perplexed eavesdropper what I mean when I say ‘I’ve been into the piano, lately’.

I also wanted to write quickly without much editing. I’d like to check back that I haven’t included anything very boring, but I’d rather not spend a lot of time on it. Let me know if you want references and please share your recommendations.

I’ll speak soon and hope you’re well.

Steven